APCA

APCA

⇦ HOME ⇧ UP ONEWhy APCA as a New

Contrast Method?

Visual readability is a critically important aspect of web content, affecting 99% of internet users. For years, the WCAG 2.x contrast guidelines provided some guidance toward readability but are being replaced for the future WCAG 3.0. Here is an overview of the need for this change and discussion of the candidate replacement, the Accessible Perceptual Contrast Algorithm (APCA).

The Contrast Problem

WCAG 2.x contrast, SC 1.4.3, and the related understandings and guidelines, were born in an era before smart phones and iPads, when displays were mostly old-school CRT type and websites used core web fonts. But that was a decade and a half ago. Today the contrast guidelines are in need of a complete overhaul due to the massive changes in computer display technology, web content, CSS functionality, and advances in vision science since 2005/2008, when WCAG 2.x was first introduced.

There are a number of reasons that WCAG 2.x contrast is faulty, one of which is the binary pass/fail nature of the SC for a property that does not apply in a binary way across perception nor impairments. Humans are not binary computers, and it is important to understand the non-linear aspects of perception, and to set guidelines that correctly model perception as opposed to “brute forcing” arbitrary values that ultimately do more harm than good.

Let’s begin with a general understanding of color and contrast with the summary outlined below. For a deeper dive see the author’s whitepaper “Introduction to Color and Accessibility” and also this comprehensive overview “The Realities And Myths Of Contrast And Color”.

What Is Readability Contrast?

Like color, contrast is not “real”, it is a perception and is more a result of how your brain interprets visual differences. It is not a simple measure of the distance or difference between two colors.

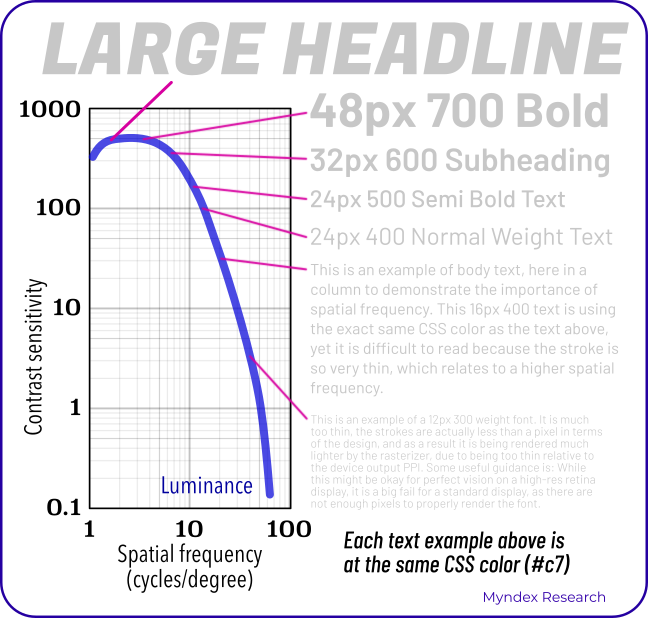

Like all perceptions it is context sensitive, meaning what is around it and its purpose affects how you see it. Contrast is also substantially affected by “spatial characteristics” which for our purposes means font weight or line thickness, and is principal factor in our brain’s lightness perception (aka luminance contrast). When it comes to color contrast, as in hue/chroma/saturation, the effect is less relevant to readability. High lightness/darkness contrast is required for fluent readability at best speed and comprehension, especially small body text in columns or blocks.

Above a certain amount, contrast constancy may come into effect wherein further increases in a mathematical contrast value does not result in higher perceived contrast for readability. A high “spatial frequency” means smaller and thinner letters. Smaller, thinner letters or graphics lowers the perceived contrast. As a result, the lightness/darkness difference between text and the background color must be increased to compensate for small thin fonts.

- Fluent readability refers to critical contrast which is that needed for best reading speed and comprehension. Dr. Bailey & Lovie-Kitchin’s studies showed, along with Dr. Legge and other recent studies, contrast must be at least ten times the contrast sensitivity threshold (CS) which is the point of “just noticeable differences” (JND). Twenty times is preferred for adequate contrast reserve above the critical contrast.

- Spot readability means being readable without significant effort, though not necessarily at the best speed or accuracy. In this case the contrast needs to be three times that of the JND.

- Various forms of visual impairment include more than acuity, which is the ability to focus the eyes to a sharp clear image. Contrast sensitivity related impairments involving the eyes or brain may have an even greater effect on overall vision.

These factors define the area of “supra-threshold critical contrast for readability.” We refer to this as “readability contrast” for simplicity. A similar supra-threshold exists for acuity in terms of font size, which is separate but in addition to the font weight as related to spatially-driven contrast.

In other words, the size of a font is related to a person’s ability to focus (defined by a number like 20/20 or 6/6 on an eye exam chart) and the size and weight of that font also directly affect contrast perception. Contributing factors are white space, letter and line spacing, the aspect ratio of the letter (tall vs wide), and other properties.

The following chart is intended to demonstrate the spatially dependent nature of human contrast sensitivity, using text samples to connect the abstract science to practical reality.

Use Cases

Spot-reading-contrast has a lower requirement than fluent readability contrast. Non-text object contrast such as for a solid icon may also have a lower lightness contrast requirement. And there are some differences in terms of the importance of color (hue or saturation) for things such as information coding.

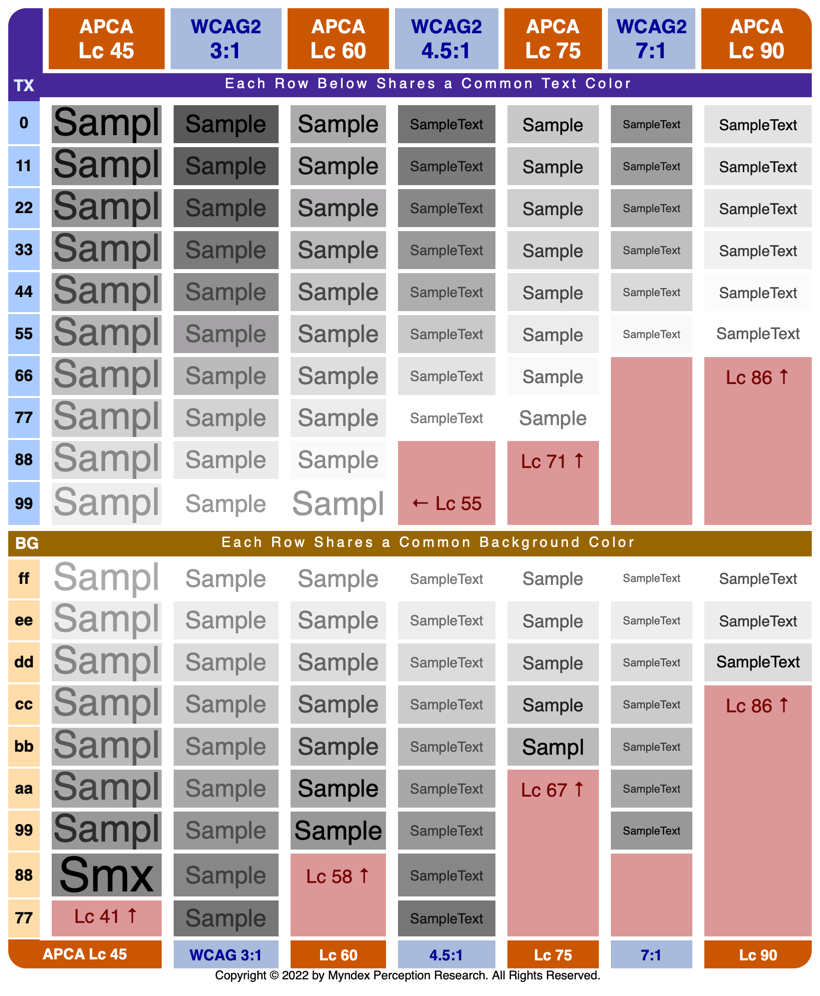

No single figure such as 4.5:1 or 3:1 can be used as a blanket target for contrast between two colors, without considering the use case, size, thickness, etc. On this point, it has been demonstrated that WCAG 2 contrast can pass colors that should fail as not readable, and sometimes the WCAG 2 math fails a color pair that should pass as very readable. Some articles with visual comparisons and examples of this are:

Contrasting Concerns

The problems of 4.5:1 as a target for a guideline not only impact accessibility, but impacts standard vision. The inherent problems with the WCAG 2 contrast math have been known for some time and widely criticized. Including studies by others showing that color insensitive types are not well served. The WCAG 2 contrast specs often cause enough problems for designers that it is ignored and today, some 86% of websites are failing WCAG_2 contrast—though some failures are not due to actually poor accessibility, but due to the incorrect math of WCAG_2 contrast.

The Solution: APCA

The Accessible Perceptual Contrast Algorithm (APCA) is a new method for calculating and predicting readability contrast. APCA is a part of the larger S-Luv Accessible Color Appearance Model known as SACAM (formerly SAPC). These models are specifically related to color appearance on self-illuminated RGB computer displays & devices, and also for modeling accessible user needs, with a focus on readability.

Lightness contrast (Lc)

The APCA generates a lightness/darkness contrast value based on a minimum font weight/size and color pair, and this value is perceptually based: that is, regardless of how light or dark the two colors are, a contrast value of Lc 60 represents the same perceived readability contrast, across the available range of colors.

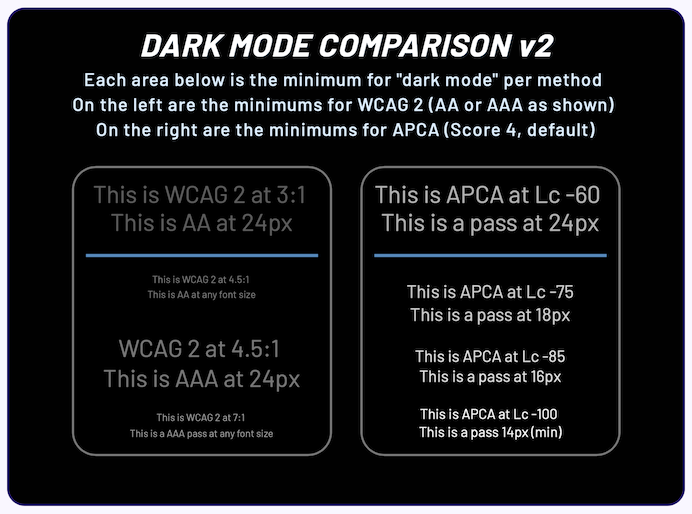

This is absolutely not the case with WCAG 2.x, which far overstates contrast for dark colors to the point that 4.5:1 can be functionally unreadable when a color is near black. As a result, WCAG 2.x contrast cannot be used for guidance designing “dark mode”. This also creates problems for color vision deficiency (sometimes called colorblind).

The APCA contrast value is perceptually uniform, and pivots near the point where the CS curve flattens due to contrast constancy. Halving or doubling the APCA value relates to a halving or doubling of the perceived contrast. There is a subtle weighting for higher contrasts to smaller, thinner fonts.

Different Uses, Different Contrasts

The APCA has a set of levels related to use cases — for instance, Lc 90 is preferred and Lc 75 is the minimum for body text. This makes for an easy way to use ACPA, very similar to 1.4.3 in terms of ease of use.

The APCA also has an optional lookup table to associate font size and weight to the readability contrast (Lc value). The lookup tables allow for even greater accuracy and therefore greater flexibility in design.

Failing Pass/Fail

A key takeaway is that a strict pass/fail with a blanket contrast ratio is not instructive as a guideline, and does not necessarily solve a given user need. In fact, user needs when it comes to contrast are conflicting—what is good for one can be harmful to another. This is even true of font size.

This points to the importance of real user personalization, an area where the technology is literally missing (and a work in progress). For the guidelines though, we can set ranges for targets and expectations toward making the web readable for all.

Visual Comparisons

In the following chart, we’re showing minimum passing contrasts for APCA and for WCAG 2. Notice WCAG 2 examples become unreadable with dark colors.

And the problem is particularly severe for “dark mode”:

Use-Case Ranges

These general levels are appropriate for use by themselves, without the need to reference a lookup table. APCA reports contrast as an Lc value (lightness contrast) from Lc 0 to Lc 105+. For accessibility, consider Lc 15 the point of invisibility for many users, particularly for thin lines, and Lc 90 is preferred for body text.

See this on ranges for a more in-depth look.

- Lc 90 • Preferred level for fluent text and columns of body text with a font no smaller than 14px/weight 400 (normal).

- Lc 75 • The minimum level for columns of body text with a font no smaller than 18px/400. Lc 75 should be considered a minimum for text where readability is important.

- Lc 60 • The minimum level recommended for content text that is not body, column, or block text. In other words, text you want people to read. The minimums: 24px normal weight (400) or 16px/700 (bold). These values based on the reference font Helvetica.

- Lc 45 • The minimum for larger, heavier text (36px normal weight or 24px bold) such as headlines. This is also the minimum for pictograms with fine details.

- Lc 30 • The absolute minimum for any text not listed above. This includes placeholder text and disabled element text. This is also the minimum for large/solid semantic & understandable non-text elements.

- Lc 15 • The absolute minimum for any non-text that needs to be discernible and differentiable, and is no less than 5px in its smallest dimension. This may include disabled large buttons. Designers should treat anything below this level as invisible, as it will not be visible for many users. This minimum level should be avoided for any items important to the use, understanding, or interaction of the site.

These define the basic minimum levels, what you might think of as A/AA in the old WCAG 2. For the equivalent to AAA, simply increase the contrast values by Lc 15. Maximum: for large fonts in dark mode, keep contrast less than Lc 90.

Range-Based Scoring

While the candidate for WCAG 3 is still in development, it includes a range-based conformance system. While it considers multiple factors, it is simple enough to be fully automated, and does not rely on an arbitrary pass/fail binary scoring.

The overall approach improves design flexibility and readability at the same time. Readability is improved by increasing contrast in blocks of body text where it is most needed, and design flexibility is achieved by relaxing contrast for large non-text elements which do not need brute-force contrast levels due to their larger size (resulting in a lower spatial frequency).

For demonstration purposes, the example tool provides real-time updates of minimum font size and weight vs contrast: apcacontrast.com click on the color patches to bring up a color-picker.

We hope this clarifies the useful differences of a perceptually accurate range-based model as the guideline for a future of best readability.

Thank you for reading,

Andrew Somers

Director of Research

Myndex Technologies

W3C Invited Expert

APCA Research Lead

THE WORLD IS READING™

Definitions of Terms Used In This Document

- Spatial or spatially: relating to size, weight, or thickness.

- Hue: the uniqueness of a given color vs other colors, i.e. blue vs red.

- Chroma/saturation: the intensity or purity of a color vs no color.

- Luminance: a physical measure of light, disregarding hue.

- Lightness: the human perception of a given luminance. Also darkness and brightness.

This document was written in basic plain language using the Hemingway app.

Study Volunteers Needed

Would you like to help create a more readable world for all? Please let us know! We have several studies planned for 2023, and it requires minimal time on your part to participate. Please send an email to perceptex@myndex.com with “volunteer” in the subject line.

NOTICE: Personal opinions expressed are the author’s and may or may not reflect those of the W3 or AGWG.

APPENDIX: Additional Reading

- Linktree of Selected Resources A good place to start.

- Main Catalog of APCA Resources and Links For the much deeper divers.

APCA Readability Criterion

Maintained by Inclusive Reading Technologies Inc., a California Non-Profit.

- Draft ARC Guidelines for implementing APCA and related technologies.

- Bronze Simple Mode is designed as an introductory mode that does not require look-up tables or matching to a reference font. Instead it’s designed as a simple set of threshold levels, similar to how WCAG 2 works but using perceptually uniform math.

Links To APCA and Related Tools

- APCA Calculator, the official technology demonstrator for APCA, includes explainers.

- Listing of Third Party Tools and Systems that have adopted APCA.

- An Accurate Colorblind Simulator based on the well respected, peer-reviewed, Brettel et alia model.

Discussion Forum

- Readability Forum questions and comments welcome.

- DISCUSS: Using APCA with other fonts Draft method for font weight conformance.

- DISCUSS: Inline text links theory and practice Draft guidance regarding link identification.

- DISCUSS: Draft Dark Mode Guidance Draft guidance regarding darkmode from light mode, and more.

- DISCUSS: Legal Issues of WCAG2 vs APCA Discussion of current and future legal status and incorporation into legislation.

Peer Review & Third Party Discussion of APCA

A listing of third party and peer reviews of APCA and related technologies. This directory includes journal-published peer-reviews, trade-published evaluations, and less formal comparative analysis, covering the usage, math, efficacy, implementation/integration, workflows, and more.

Published Articles on Color & Contrast by A.Somers

- The Realities And Myths Of Contrast And Color Published by Smashing Magazine. A brief but comprehensive primer to vision, color, and contrast for design, with an emphasis on typography, readability, and visual accessibility needs.

-

Better Reading on the Web Published by UX Collective, this article discusses and demonstrates issues with automated testing and WCAG 2 contrast math, methods, and guidelines.

- The Tangled Web tech blog (TangledWeb.xyz):

- Please Stop Using Grey Text This popular article debunks one of the worst myths regarding design contrast.

- What’s Red & Black & Also Not Read? examines the nature of color insensitivity and readability.

- Busy Background Breaks Bulletin Examples of how to destroy readability by choosing the wrong image as a background. And also, how to fix it.

- Hats off to ALL CAPS myth-busting misunderstandings regarding dyslexia, are special dyslexia fonts even useful, and the shift from using ALL UPPERCASE LETTERS for various text elements.

- A Contrast of Errors looks at the history and the current international readability crisis.

- Contrasting Theories Background on the first two years of R&D.